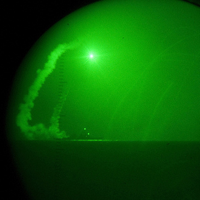

The battle to define the lessons of the Western intervention in Libya began almost as soon as the first Tomahawk missiles started hitting that country’s air defense network back in March. Many of the arguments have focused on the viability of the “Responsibility to Protect” doctrine of international humanitarian intervention and how it might apply to such countries as Bahrain or Syria. However, defense analysts also subjected the military character of the campaign to scrutiny, with some now suggesting the fight in Libya indicates that airpower has finally fulfilled its decisive promise, having matured to the extent that it can win wars with only a minimal ground component. According to retired USAF Lt. Gen. David Deptula, “Whether one agrees or not with the intervention, one thing is clear -- and no surprise to objective observers: Modern air power is the key force that led to the overthrow of the Gadhafi regime.” The effect of such a conclusion on austerity-afflicted military budgets in Europe and the United States could be huge and costly, as it is almost certainly premature.

In a previous op-ed written before the intervention with the Heritage Foundation’s Mackenzie Eaglen, Deptula notoriously argued that any no-fly zone over Libya should employ U.S. Air Force F-22 Raptors. Ironically, that aircraft was grounded for safety reasons for the bulk of the Libya campaign. Deptula and Eaglen’s piece represented a bald argument on behalf of the institutional interests of both the U.S. Air Force and Lockheed Martin, the producer of the F-22, but when made in less-cartoonish fashion, the case may have an effect on future procurement decisions.

Some are already using the Libya precedent to argue for military intervention in other countries. For example, Sen. John McCain has called for action against the Syrian government, presumably along the lines of the Libya operation. When individuals like Deptula claim that airpower has won the day without sufficiently examining the complexity of the case, they make McCain’s posturing more politically viable. In the United Kingdom, as well, the Royal Air Force was quick to take credit for rebel victories, using its experience as ammunition in the never-ending struggle for resources between the RAF and the Royal Navy.